The exhumation data tell us that after the First World War, more than 170 soldiers were exhumed in the grounds of the Zonnebeke Chateau.

From 30 April to 15 November 2023, a temporary exhibition in the Passchendaele Museum and a walk through the grounds throw light on this extraordinary story. Places were bodies were exhumed are marked with ‘reflection points’, beacons recalling the tragedies that took place there.

This online exhibition looks in more depth at events in the grounds in 1917.

The project is part of the First World War theme of Toerisme Vlaanderen en Westtoer for 2023 and 2024:

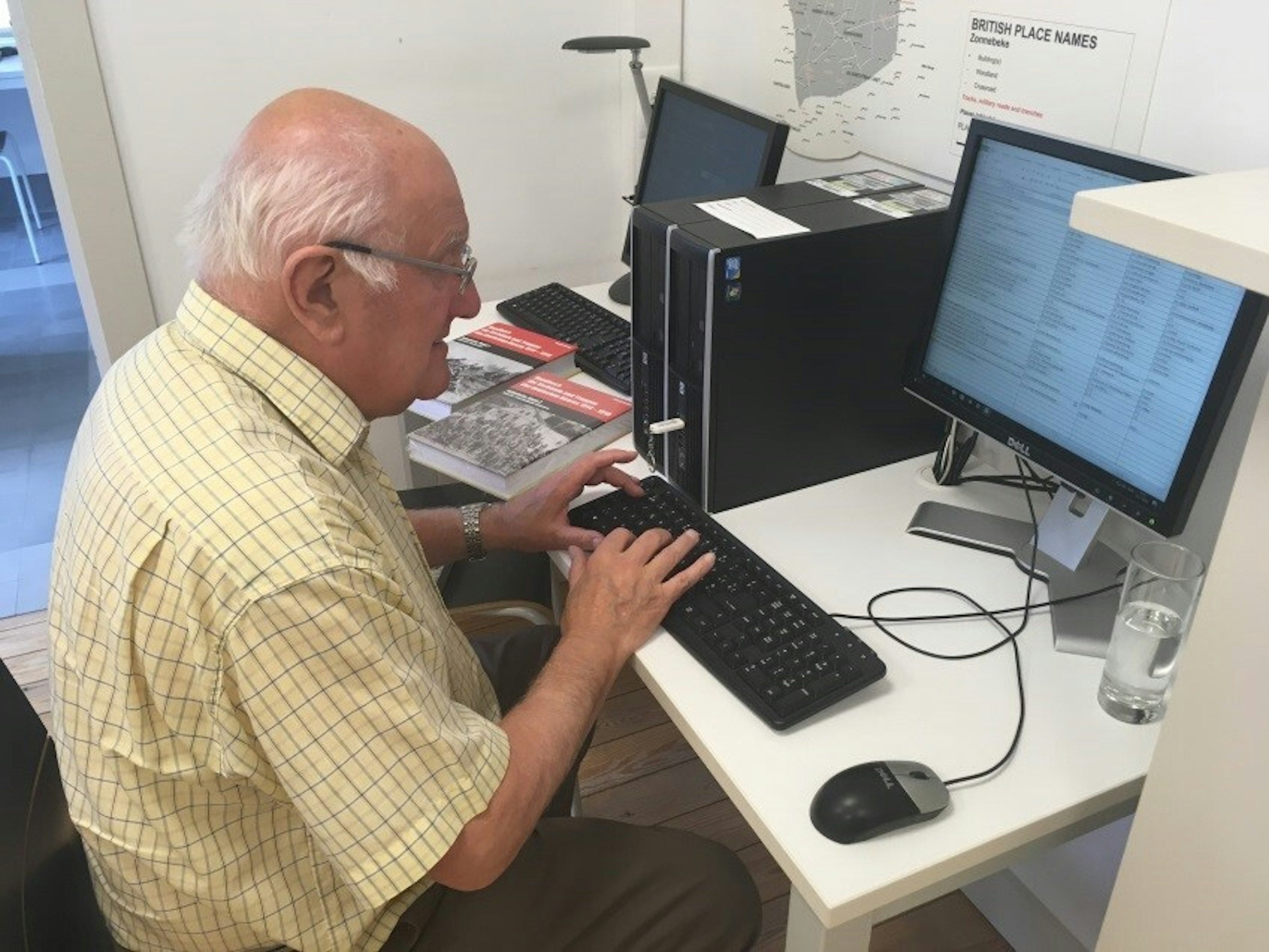

In early 2019, volunteer Frans Descamps was asked to make an inventory of exhumation data on behalf of the Passchendaele Museum. He spotted a namesake he had come upon before, William Fraley Deschamps. Research showed that William’s body was exhumed in the grounds of the Zonnebeke Chateau after the war.

Volunteer Frans carried out further research into William Deschamps and wrote an article for Schrapnel, the magazine of the Belgian Western Front Association (WFA België).

Frans’s enthusiasm was contagious, prompting the museum team to make greater use of the exhumation data for the dead in the grounds of the Zonnebeke Chateau, which houses the Passchendaele Museum.

William Deschamps

William Deschamps

William Fraley Deschamps, a former carter, was born in 1892 in Coonambelah, Queensland, Australia. He was the youngest son of August Victor Deschamps and Rose Hind. His father August was born in Caen, Normandy, France and emigrated to Australia when he was 15 years old. William’s mother Rose originally hailed from England. Her family moved to Australia in the 1870’s. On October 23, 1916 he enlisted in Townsville, Queensland and embarked from Sydney on board HMAT A64 Demosthenes on December 23, 1916, with the 18th reinforcement of the 25th Battalion, part of the 7th Australian Brigade of the 2nd Australian Division. His brother, Wallace Victor, died of disease in Cairo, Egypt.

William joined up in October 1916 and served in the Australian Infantry 25th Battalion, part of the 7th Australian Brigade, of the 2nd Australian Division. From September onwards the Division participated in the Battle of Passchendaele and on 20 September 1917 it attacked Anzac Ridge with two Brigades, the 7th Australian Brigade on the right and the 5th Australian Brigade on the left. Its jump off line was just east of the hamlet of Westhoek. The attack of the 7th brigade was carried by the 25th Battalion; the 27th was in support and the 28th in reserve.

The 25th Battalion advanced at 5.40 a.m. They moved through the Haenebeek valley and the northern outskirts of the Nonne Bosschen. They met little resistance and managed to consolidate the Red Line by 6.10 a.m. Not an hour later the 27th Battalion passed through and went to the Blue Line. They were equally successful. By 8.10 a.m. the 28th Battalion advanced from Westhoek Ridge. They captured and secured the final objective by 10 a.m.

The attack had been a success. Even the German artillery had been fairly quiet during the attack, but around noon the Germans started shelling the captured ground and two posts in the 25th Battalion’s line took a direct hit. The men of the 25th held their ground and were relieved during the following night. Notwithstanding the success of the attack, the Battalion had suffered heavy casualties. Thirty-three men were killed, ten men died of their wounds, 128 men were wounded and four men went missing.

William Fraley, aged 25, was killed in action on September 21, 1917. He was initially buried on the Zonnebeke Chateau grounds, just west of De Knoet Farm (28.D.28.a.70.60), which was still held by the Germans at the time. Possibly he was captured on September 20. His remains were exhumed and reinterred at Tyne Cot Cemetery; Plot 25, Row H, Grave 20.

The sources

For almost all the dead of the Commonwealth who were moved to a consolidation cemetery after the war, a burial return sheet is available. The coordinates on this document show fairly precisely where a body was initially buried during the war.

The place of exhumation gives more insight into how a person was killed, as well as enabling us to mark the position in the present-day landscape, with the aid of trench maps and modern digital applications. We can also use burial return sheets to work out how many bodies were found at a given location.

© Commonwealth War Graves Commission

© Commonwealth War Graves CommissionInventory

In 2019 the Passchendaele Museum received from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission a digital copy of all the burial return sheets for the cemeteries in which we know that men killed at Zonnebeke now lie.

Volunteer Frans Descamps worked through the thousands of documents, searching for relevant coordinates. In a simplified search area of around one square kilometre he identified 346 exhumed Australians, British, Canadians and South Africans. We know the names of around 40% of them.

For every deceased soldier he found, Frans carefully noted the details of their exhumation. This was the basis for the geopositioning of the field burials in the chateau grounds and the in-depth research that followed.

And the Germans?

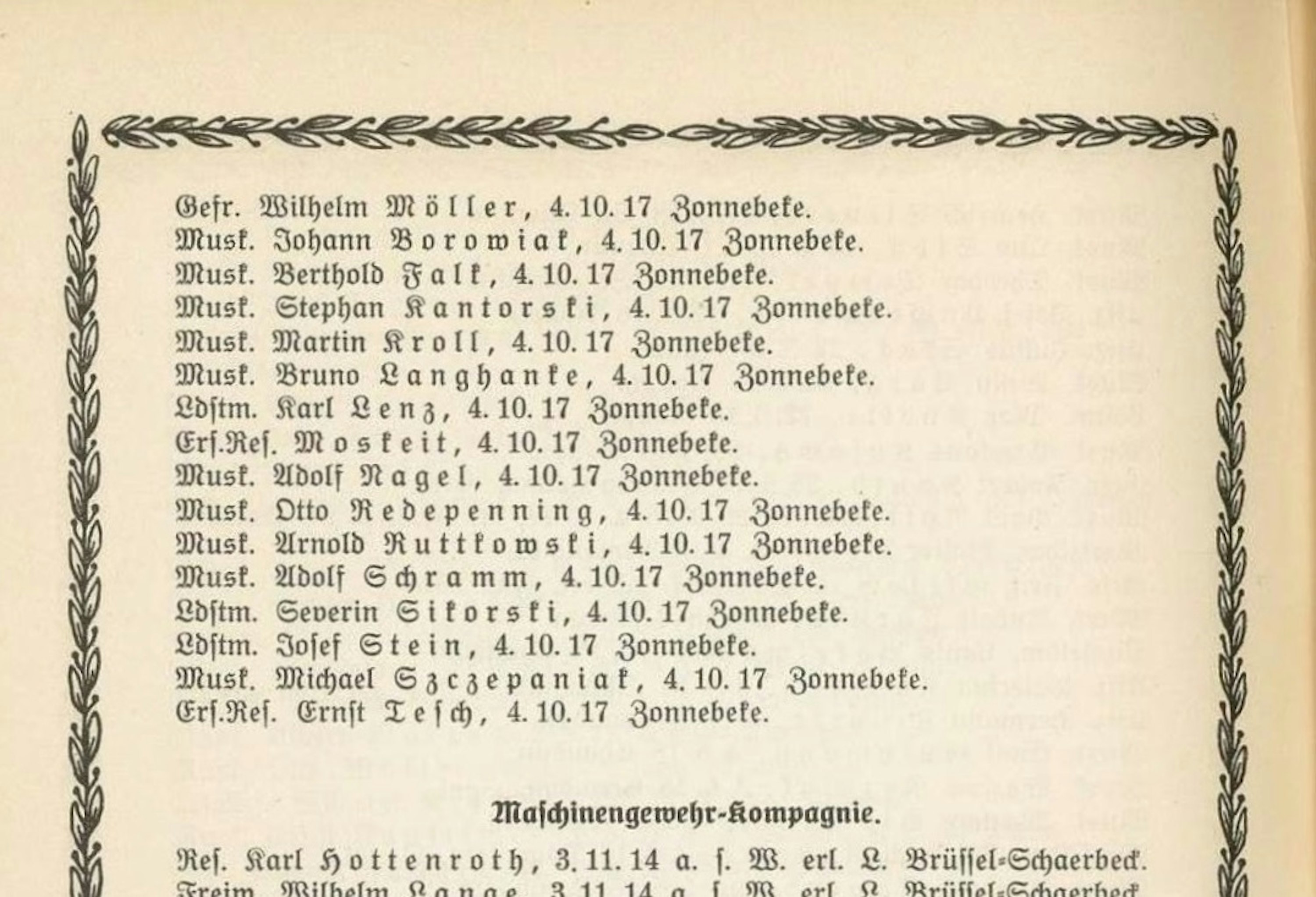

The number of Germans exhumed at Zonnebeke after the war was probably just as great. There are as yet no known details about German exhumations.

Hundreds of Germans died in the search area. Their graves have disappeared, or their mortal remains have not been identified. It is possible that many of them lie buried in German cemeteries as unknown soldiers.

The figures speak for themselves. Of the 356 dead of Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 212, which on 4 October 1917 stood ready to attack in and around the chateau grounds, just one in ten has a known grave. Fewer than two in ten are commemorated on a monument to the missing.

Lacking details of the exhumations, we cannot give the many German dead in the grounds of the chateau a ‘reflection point’. We have however inventoried their names and integrated them into this project. Because in a war there are no winners or losers.

© MMP1917

© MMP1917Beacons of memory

Between 30 April and 15 November 2023, ‘reflection points’ in the chateau grounds mark the places where bodies were exhumed after the war. They are beacons that recall the tragedies that took place there.

A walk leads through this land art installation, which has been put in place by volunteers of the Passchendaele Museum. Along the way you get to know some of the men who fought and died close to the museum.