The grounds of the Zonnebeke Chateau have a long history. Until the war broke out, this was an oasis of peace. The land was owned by the Iweins family, which had a luxurious chateau built on it. In the surrounding landscaped parkland were fanciful outbuildings, a poultry yard and a walled vegetable garden with a greenhouse.

On 20 October 1914 the Iweins family, along with most of the inhabitants of Zonnebeke, fled the violence of war. Several days later, fierce fighting took place in the grounds of the chateau.

On the firing line

At the start of the First Battle of Ypres, the Zonnebeke Chateau and its grounds briefly fell into German hands. The Germans used the outbuildings and the many patches of woodland as cover and deployed snipers.

On 24 October 1914 the Germans were driven out of Zonnebeke by British and French troops. The village then remained in Allied hands for several months. During the winter, the French occupied the area, enduring appalling conditions.

We do not know of any identified field burials in the chateau grounds from this period. It is impossible to imagine, however, that during that time no men were killed within the grounds. We have no way of finding out exactly who died here during the first years of the war.

© MMP1917, MZ 08989

© MMP1917, MZ 08989Steady deterioration

In 1915 the British troops withdrew from Zonnebeke, so the chateau grounds came to lie several kilometres behind the front. For German troops who were rotated out of the line, this was the ideal spot to rest and recuperate. Music shows were organized and there was boating on the lake. In the chateau, which was furnished as a casino, officers tried their luck.

Meanwhile, to the east of the grounds, the Flandern-I-Stellung was built, a heavily defended series of bunkers. Several bunkers were built in the chateau grounds, including the spacious cellars of the farmhouse.

In 1917 the area became more turbulent. Zonnebeke increasingly came under fire. From 31 July 1917 onwards, with the start of the Battle of Passchendaele, the village became a target of British artillery fire. The grounds of the chateau were steadily transformed into a moonscape.

-

![DSC 1223]() © MMP1917

© MMP1917A wall clamp from the pre-war chateau farmhouse. -

![12 Park Juli17]()

The chateau grounds in July 1917.

Norman Cruddas

Norman Cruddas

Norman Cruddas was born in 1880 in Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India. He was the son of John and Annie Wilson. In 1891 he lived in a boarding house in Hove, Sussex, England while attending the Sutton Valence School, where he is listed on the memorial. His family lived in Troon, Ayrshire, Scotland, where Norman is remembered on a memorial in St. Ninian's Church. Before the war Norman emigrated to South Africa. He took part in the Second Boer War and served as a Trooper in the 22nd (Cheshire) Company of the 2nd Battalion Imperial Yeomanry. Norman enlisted on 19 September 1915, later being commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 3rd Regiment South African Infantry, part of the South African Brigade, of the 9th (Scottish) Division.

On the 20th Of September 1917, the 9th (Scottish) Division participated in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, a phase in the Third Battle of Ypres. Two of its Brigades were to take part: the 27th and the South African Brigade. The 27th Brigade attacked with the 6th King’s Own Scottish Borderers and the 9th Scottish Rifles; the 12th Royal Scots were in support. The leading battalions of the South African Brigade were the 3rd and 4th South African Regiments, with the 1st and 2nd South African Regiments in support. The objective of the South African Regiments was the Red Dotted Line, running roughly along the Hanebeek Stream. The 4th South African Regiment would attack from the left, while the 3rd South African Regiment would attack from the right.

The 3rd South African Regiment reached the front-line trenches at 11.30 p.m. on the night of 19 September. They held the line from a point about 200 metres east of Low Farm, running southeast until the Bourgognestraat, north of Railway Dump. “C” company (under Captain Ellis) was placed on the left, “B” company (under Captain Sprenger) in the centre and “A” company (under Captain Vivian) was placed on the right. “D” company (under Captain Tomlinson) was in support, but one platoon was attached to each of the attacking companies.

At 5.40 a.m. the attacking Battalions advanced behind a barrage. The left wing of the 3rd South African Regiment advanced without heavy opposition. They captured Vampir, crossed the Hanebeek stream and captured Mitchells Farm at about 6:15 a.m. The situation on the right wing was more difficult. “A” Company and a part of “B” and “D” Company reached their objectives, but could not advance any further as the 12th Royal Scots were held up by opposition from Potsdam. “A” Company was ordered to capture Potsdam, but this attack disintegrated, causing heavy casualties. The strongpoint was eventually captured with assistance from “B” Company, although also incurring heavy casualties. The Germans troops evacuated Potsdam, running up Zonnebeke Railway. The remaining troops and machine guns were captured. Potsdam was left in charge of the 12th Royal Scots so the companies could again move towards their objective east of the Hanebeek stream. By nightfall, the 9th Division managed to consolidate all objectives. At 5 pm there was a German counterattack, but it was soon stopped by artillery. The 3rd South African Regiment was relieved on the night of 21st/22nd September.

Norman Cruddas, aged 37, was killed in action on September 20, 1917. He was leading “D” Company during the attack on Potsdam when he was killed. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission believes that Second Lieutenant Cruddas was buried among four other South African soldiers near Brick Kiln & Yard, Zonnebeke at 28.D.28.a.4.1. His remains were exhumed and interred at La Brique Military Cemetery No.2, plot I, row Y, grave 2.

Battle of Polygon Wood

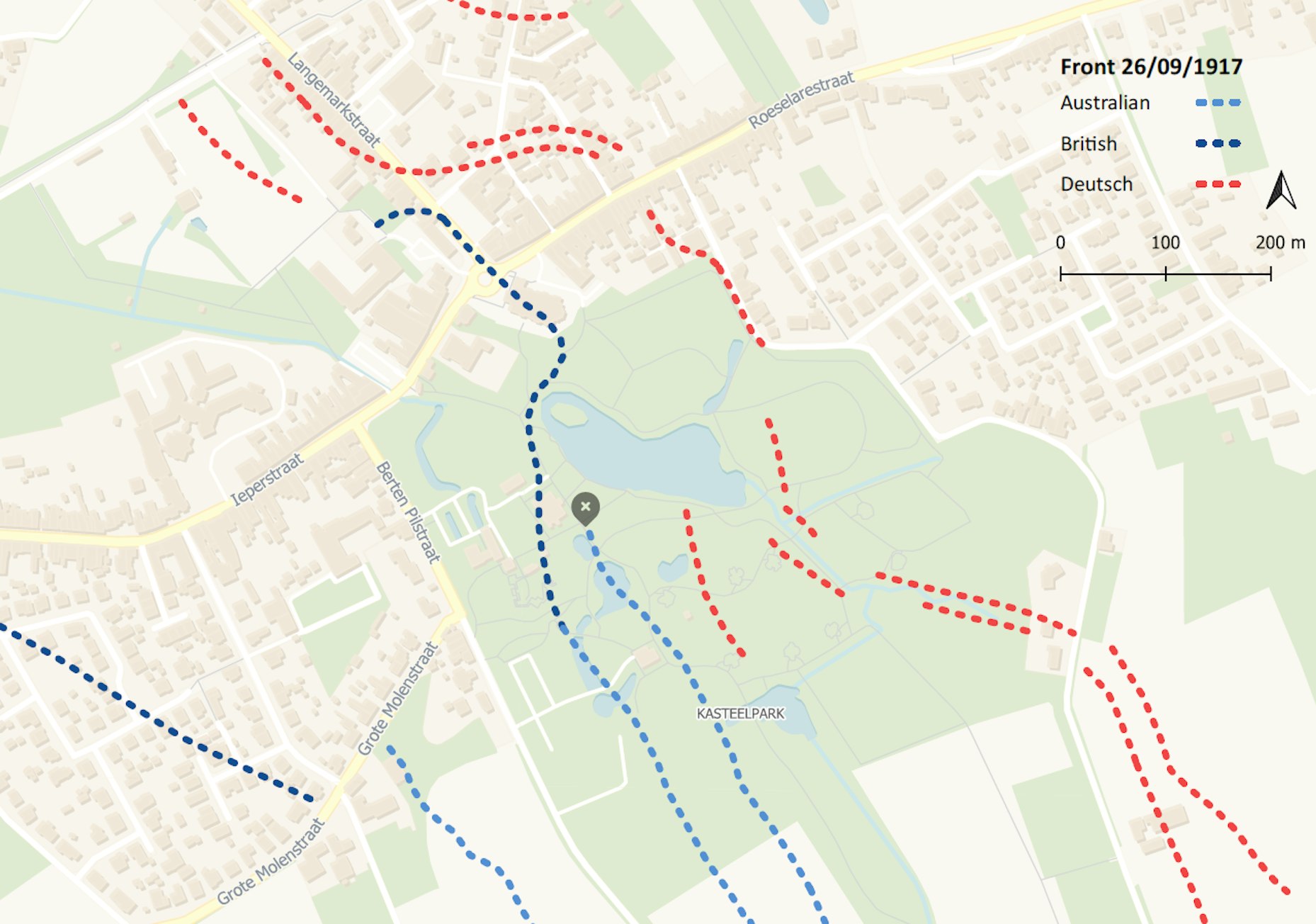

On 26 September 1917, British and Australian troops reached Zonnebeke. That day the Germans were caught off guard and thrown into chaos. Many were forced to surrender. Yet there was stiff resistance, especially in the ruins of the village and in the grounds of the chateau.

In Zonnebeke the Allied front stabilized at the intended objective. The ruins of the church, a strategically important place, were now in British hands. They were transformed into a machine gun nest. Every German attempt to retake the ruins of the church was repulsed.

The exhausted Germans did not succeed in breaking the Allies’ grip on Zonnebeke. Heavy British machine gun fire, the poor state of the terrain, which was boggy at best, and the thick barbed wire entanglements made any counterattack impossible. Small groups of attacking Germans were shot to pieces and any survivors had to take cover in shell holes.

At around 17.00 hours German time, the counterattack essentially came to a standstill. Over the next few days, the troops were relieved. Every visible movement was fired upon, but there was no major offensive for the time being.

-

![DSC 1228]() © Collection of Lee Ingelbrecht

© Collection of Lee IngelbrechtShell head with original colouring, found along the Foreststraat to the east of the chateau grounds. -

![Kaart 1]()

26 September in Zonnebeke.

A high human toll

At least 450 British and Australians, and more than 550 Germans, were killed in and around the village and the chateau grounds on 26 September.

Even more were wounded or captured. The German Füsilier-Regiment 34 suffered 738 losses, including almost 500 wounded or taken as prisoners of war. The regimental staff, occupying a bunker near Broodseinde, were so deeply affected by the cries of the wounded that for days they were barely capable of issuing orders.

In the chateau grounds, no man’s land was littered with the wounded, who shouted for help. A group of Germans with a Red Cross flag made its way around the lake while the fighting was still going on, to provide first aid.

Many were shocked by what took place at Zonnebeke. Some, like one hardened German officer, lost their voice. Others went mad. Even Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith, commander of the 10th Royal Welsh Fusiliers, was evacuated with shellshock.

The Infanterie-Regiment 452 was ordered to launch a counterattack at Zonnebeke on 26 September. One of the men noted down what he saw when his unit crossed the ridge at Broodseinde:

Over the marshland before Zonnebeke a hurricane of fire raged, at the sight of which even the most courageous held their breath for a moment. From a steeply sloping spur, heavy mortar shells gurgled down, clusters of on average 15 cm calibre shells threw up high fountains of water and mud, gas grenades hissed between them and in the air, tier upon tier, stood a wall of exploding shrapnel shells set to detonate only a few metres above the ground.

No one who fought in Flanders will forget as long as he lives the sight of this storm at Zonnebeke. The chin strap of their helmets pulled tight, their heads ducked low, the companies jumped and tumbled in separate squads through the wall of fire. Here the shrill cries of those hit – who could attend to them in such moments? There a great heavy chunk whirls several men into the air high as a house and hurls them to the ground smashed to pieces. – There a gas zone appears. A hoarse command: ‘Gas masks out!’ The empty lungs refuse to work under the mask. Here a man collapses, coughing: ‘I can’t go on.’ He is dragged to his feet by a rough fist: ‘Go! Forwards! For dear life.’ Onwards and through…

© MMP1917, MZ 13476

© MMP1917, MZ 13476

Joseph Lapworth

Joseph Lapworth

Joseph Frederick Lapworth, a former clerk, was born in May 1894 in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. He was the son of Sarah Lapworth. He served in the Citizen Military Forces (9th Infantry). On February 16, 1916 he enlisted in Brisbane and he embarked from Brisbane on board HMAT A42 Boorara on August 16, 1916, with the 4th reinforcement of the 49th Battalion, part of the 13th Australian Brigade of the 4th Australian Division.

The 4th Australian Division participated in the Battle of Polygon Wood, a phase of the Battle of Passchendaele. It was to attack from positions along Anzac ridge, just south of Polygon Wood, and operated on the left flank of the 5th Australian Division, which had to capture Polygon Wood itself. The 4th Division’s attack was carried by the 4th and 13th Australian Brigades. The 13th Australian Brigade in turn advanced with the 50th Battalion; the 49th and 51st Battalions Australian Infantry were in support.

On 26 September 1917 at 6.45 a.m. the Australians moved forward behind a creeping barrage. The barrage was very dense and powerful, and most German resistance was broken even before the attacking parties arrived. The defenders they did encounter, surrendered willingly. Only some German snipers offered slight resistance.

At 7.55 a.m. the 49th Battalion had moved through Albania Woods and reached its objective, just west of the hamlet of Molenaarelsthoek. Once the men had established their positions they started digging trenches and organized the defence. At 3.30 p.m. and at 6.00 p.m. Germans were seen massing on their front, but both attempts to organize a counterattack were checked with artillery fire. For both Australian Divisions the attack on the 26th of September had been a success. Polygon Wood had been captured by the 5th Australian Division and all Battalions of the 4th Australian Divisions had reached their objectives.

The 49th Battalion was relieved on the night of the 27th of September by the 46th Battalion Australian Infantry. Notwithstanding the success of the attack the 49th Battalion suffered a total of 129 casualties. Twenty-five men were killed, five officers and 94 other ranks were wounded and five men went missing.

Joseph Frederick, aged 23, was killed in action on September 26, 1917. According to his companions, he was the last to jump into the shell hole and got shot in the back. They dressed his wound and got him on a bearer stretcher, but they were hit, wounding Joseph Frederick again very badly. According to Private Moriarty (stretcher bearer) he was just able to say “They have got me again.”. They got him back in the shell hole where he died a few minutes later. Private Lapworth was initially buried where he fell, west of Remus Wood (28.D.28.d.10.10). A rough cross was made with a stick and a German bayonet. After the war, his remains were exhumed and reinterred in Bedford House Cemetery, Enclosure No. 6, Plot 3, Row A, Grave 8.

4 October 1917

The Allies were convinced that occupying the ridge at Broodseinde would be decisive for their Flanders offensive. The initial plan was to take it on 6 October, but with autumn weather approaching and a greater risk of bad weather to come, the attack was brought forward by two days.

Meanwhile the German defenders were in a tight spot. At Zonnebeke the Flandern-I-Stellung was in full view of the enemy. This made it extremely difficult to bring up troops and materiel.

The German army leadership was forced to take drastic measures, in the form of a major counterattack at Zonnebeke that was named Unternehmung Höhensturm. Höhensturm means ‘a storm at a great height’.

© Tate Gallery, T07694

© Tate Gallery, T07694 © Tate Gallery, T07694

© Tate Gallery, T07694

© MMP1917

© MMP1917

© Collection of Lee Ingelbrecht

© Collection of Lee Ingelbrecht