© AWM E01237

© AWM E01237In search of a breakthrough in Flanders

On 31 July 1917 the day came. More than 4.2 million shells were fired at the German positions. The shelling failed in its aim. Bunkers remained intact while the landscape was churned up and the drainage system destroyed. A series of summer downpours turned the field of operations into a morass. Animals, men and equipment sank into the mire.

After weeks of trudging through the mud, New Zealanders, Australians and South Africans joined the exhausted British divisions. Momentum was gained briefly, but then the attack stalled again. 12 October saw a particular fiasco when New Zealanders and Australians advanced onto the fortified high ground at Passchendaele. The British breakthrough towards the Flemish coast was in danger of ending in failure.

Passchendaele

For the army high command, halting the offensive, however many lives that might save, was not an option. A victory, even a symbolic victory, was vital. Field Marshall Haig’s eye fell on Passchendaele. The heavily shelled village on top of the West Flemish ridge had been in German hands since 1914 and had assumed mythical proportions.

To win that prize, Haig turned to the Canadians. Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps, was not amused. When Haig approached him, he responded as follows:

"Passchendaele! What’s the good of it? Let the Germans have it – keep it – rot in it! Rot in the mud! There’s a mistake somewhere. It must be a mistake! It isn’t worth a drop of blood."

© Smithsonian American Art Museum

© Smithsonian American Art MuseumBut Currie had no choice. He reluctantly accepted the task, on condition that he would be given time and above all more artillery. More than one gun for every four metres of front line.

In an early phase the troops would have to extricate themselves from the mud. Once they had reached higher, dryer ground, Passchendaele would be theirs for the taking. The stretch of high ground north of Passchendaele was to be won in a final phase.

‘I fell into the bottomless mud, and lost the light’

Nothing could have prepared the Canadians for the hell of Passchendaele. Nearby villages, which some of them remembered from 1915, had been wiped off the face of the earth. The roads had been reduced to muddy water courses, and positions were flooded or non-existent. German artillery bombarded the supply lines.

In the early hours of 26 October 1917 the guns belched out their deadly load. The defending forces withdrew to their shelters. When the thunder of the artillery died away and the Canadians moved forward, the Germans manned their machine guns. Resistance was fierce; the losses were correspondingly great.

Bellevue, essential to the defence to the west of Passchendaele, fell. The Canadians dig in on the side of the ridge.

The renewed advance of 30 October was tortuous. Plodding through the mud, the men were an easy target. Yet there were successes. They took Crest Farm, a heavily defended stronghold between them and Passchendaele.

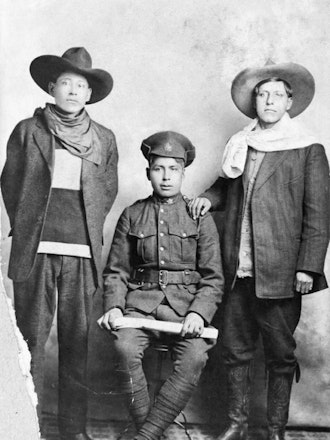

Mike Foxhead

Mike Foxhead

Despite needing more manpower, the Canadian Army was hesitant about allowing Indigenous peoples to join its ranks. The unprecedented losses changed that. The decision was made to recruit actively among the Indigenous population.

Conversely, there was great distrust of the government among the First Nations of Canada, the Inuit and the Métis. The tribal nations were indifferent or even downright hostile to a war that had nothing to do with them. Yet the recruitment campaign on the reservations was a success. Many young men were eager to prove themselves and volunteered to join up.

Eighteen-year-old cattleman Mike Foxhead joined the 50th Battalion (Calgary) in September 1917.

In the dead of night, Mike’s unit arrived at Ypres on 21 October 1917. After a short break for tea and rations, his battalion moved further eastwards, deeper into the nightmare. Before they could properly occupy their positions, the men came under fire. The force of the explosions wrenched the gas masks off their faces and many young men were gassed.

The next day Mike found himself in the front line close to Tyne Cot. Conditions there were terrible. The Canadians were crammed together to wait for the attack of 26 October. The units were under constant fire. One survivor of the 50th Battalion described the march to Passchendaele as follows:

‘Mud and weeping skies joined in the wretched cacophony of bursting shells, screaming bullets, shattering shrapnel, and the tortuous cries of the wounded and the dying. … Men were crazed, some driven stark insane. Unmitigated hell reigned.’

Mike Foxhead, barely 19, died on 23 October 1917. He was given a field burial near Tyne Cot.

© BAC LAC O-3751

© BAC LAC O-3751‘We penetrated deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness’

On the cold morning of 6 November, the Canadians launched their ultimate attack on Passchendaele. German positions were surrounded and, supported by light machine guns and mortars, the infantry did its job. The motto was ‘fire and movement’.

Targeted shelling, thorough logistical preparation and shock-troop tactics bore fruit. The ruins of Passchendaele were taken. Yet the losses were unutterably heavy.

John William Collins & William Lister Morrison

John William Collins & William Lister Morrison

The 2nd Battalion (Eastern Ontario Regiment) suffered 267 dead, wounded and missing within just a few hours. Thirty-year-old John Collins and William Morrison, ten years his junior, died close to their objective. They were buried together along the Paardebosstraat, close to what the British called Valour Farm.

Wounded Canadians at Passchendaele, 1917.

Conclusion

The Germans could take no more. They raised their hands en masse. After three months and losses of 600.000, including more than 175.000 dead, the Allied high command had its trophy. In just a few weeks, 4.000 Canadians had been killed, more than 12.000 wounded and countless others marked for life.

"I spent thirty-one months in France and Belgium and I would do all of the rest over again rather than those six weeks at Passchendaele."

© BAC LAC O-2214

© BAC LAC O-2214